Precursors to the original Aberri Eguna or the “Day of the Homeland” first held in Bilbao were political demonstrations led by Basque exiles in South America during the late 1800s, according to an expert on Basque culture.

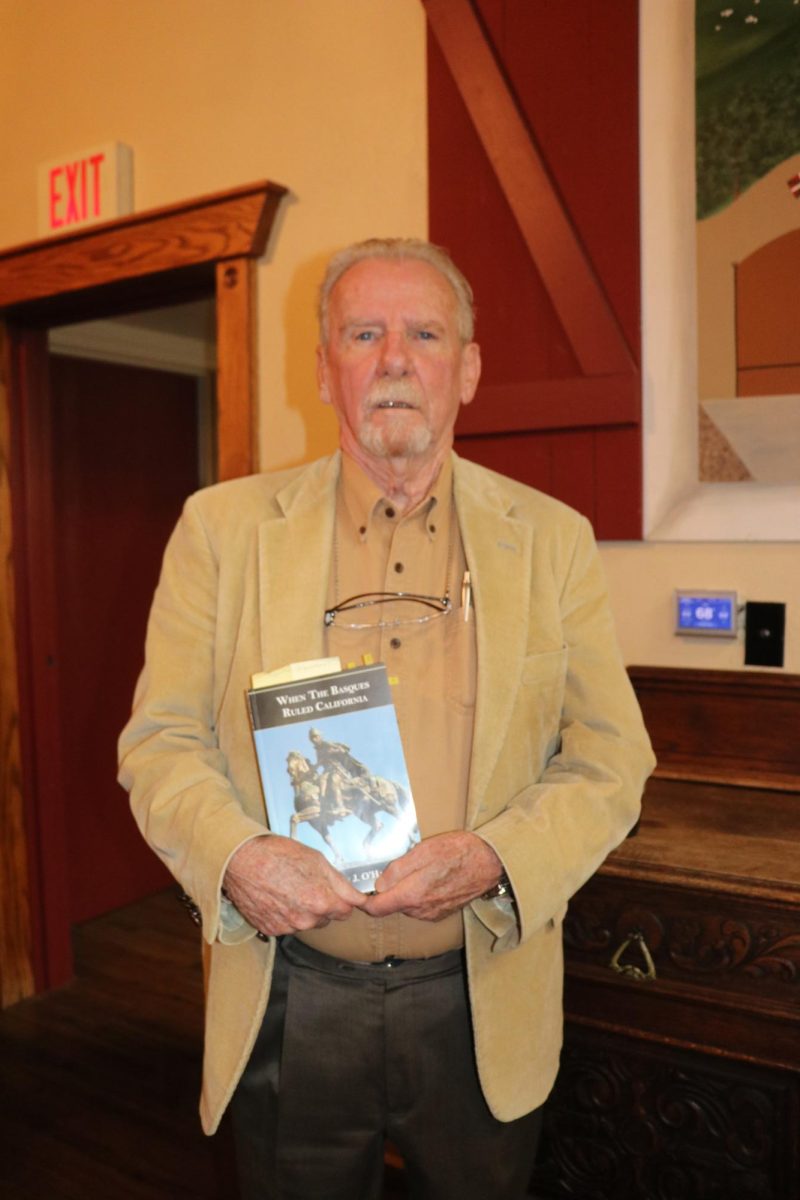

Born to a Basque father who was forcibly sent to Caracas, Venezuela by Spanish authorities, Dr. Xabier Irujo, Chair of the Center for Basque Studies at University of Nevada in Reno, said it is important to recognize the efforts of exiled Basque ancestors in the development of this important Basque nationalist holiday.

“My father was very much involved in the organization of Aberri Egunas in the Basque Country from 1964 to 1974 during the dictatorship” of General Francisco Franco, recalled Dr. Irujo in an interview with Euskal Kazeta. “He was exiled in Venezuela because of…organizing the Aberri Egunas,” he said of his father Pello Irujo Elizalde who also was left temporarily blinded after being tortured by police in Pamplona, Spain in 1967. As a member of Euzkadi Buru Batzar (EBB) – the national committee of EAJ-PNV, Irujo’s father was on Spanish authority’s radar as a Basque nationalist involved in organizing political events. Following his subsequent exile in Venezuela as well as being fined 10,000 pesetas, Irujo’s father continued to organize Aberri Eguna celebrations locally and abroad, as did other exiles.

Aberri Eguna was originally celebrated on Easter Sunday 1932 in Bilbao, as a natural outgrowth of the Basque nationalist movement, precipitated by political and cultural repression of the Basque ethnic minority within Spain and France. Dr. Irujo pointed out that Aberri Eguna is less a celebration than a demonstration protesting the historical wrongs that came from the Basques’ loss of freedoms.

“It was a demonstration requesting a statute of autonomy for the Basque Country,” asserted Dr. Irujo. “That was the first day of the Aberri Eguna,” he said referring to the widely known Bilbao celebration, “but it is not exactly the first one ever celebrated.”

According to Dr. Irujo, the Basque region began to lose some of their rights in 1789. The provinces of Iparralde (today part of the French republic) — Lapurdi, BaxeNafarroa, Zuberoa — were eliminated following the end of the French Revolution, and the southern Basque provinces (Hegoalde) of Gipuzkoa, Bizkaia, Alaba and Nafarroa lost their independence between 1841 and 1872.

Additionally, leaders like Alfonso XII (1874-1885), Alfonso XIII (1886-1931) and dictator General Francisco Franco (1936-1975) doggedly continued systemic cultural repression of the Basque people by utilizing such tactics of cultural genocide as prohibiting the use of the native Basque language Euskara and setting curfews to deter groups from organizing.

This tamping down of cultural expression served to strengthen the resolve of those who had earlier been exiled to South America (Uruguay, Argentina, Chile and Venezuela), as a result of the Second Carlist War (1872-1876). It led them to develop the first Basque cultural centers in the late 1800s. They were also the first Basques who celebrated the precursors to Aberri Eguna. They called them “Fiestas Euskaras” or “The Basque Festivals.”

MORE FROM EUSKAL KAZETA

What is the Basque Country?

Basque Lectures by Dr. Irujo at Boise State

“They were organized for the first time by the politician and diplomat Antoine d’Abbadie in Iparralde who wanted to foster patriotic activities in favor of the Basque culture, language, and music after 1853,” Dr. Irujo explained. “By 1881, Basques exiled in the Americas, mainly in Uruguay and Argentina, started to organize these festivals in Montevideo and Buenos Aires with a much stronger political aim. In Argentina, for example…we have a big celebration that can be considered one of the first Aberri Egunas,” said Dr. Irujo of the celebration of Nov. 1, 1882 in Buenos Aires.

The festivities for “The Inauguration of the Plaza Euskara”, as this specific demonstration was called, included the planting of the Tree of Gernika – an oak tree symbolizing the ancient liberties of the Basque Country – while attendees sang its namesake song by Basque poet and singer Joxe Mari Iparraguirre, said Dr. Irujo.

“It was a very political celebration with a very concrete aim,” said Dr. Irujo. “And that was to request an institute of autonomy, but we can call it a constitution for the Basque territories within the Spanish state.”

These days Aberri Eguna is more widely and freely celebrated than it was prior to the end of Franco’s dictatorship. It is often celebrated with a Catholic mass, protest walk, flag raising, music, dance, and a large meal — though these elements depend strongly on the organizers. But the most important element, as Dr. Irujo puts it, is the “political vindication” of the Basque people and country.

Additionally, drawing on symbolic parallels between the resurrection of Jesus, Aberri Eguna is celebrated on Easter Sunday as nod to the rebirth of the Basque Country and the recognition of its sovereignty.

In the United States, the New York Basque Club is the first and possibly only club to regularly celebrate Aberri Eguna over the years. Dr. Irujo said that this dedication to the holiday may be the result of the proximity of a more politically active Basque community to the Basque delegation which was exiled to New York during the Spanish Civil War.

“It is a very important celebration during which this proclamation of the rights of independence takes place,” said Dr. Irujo. “So it is very important for everyone in the [Basque] country and outside the [Basque] country.”

Following the death of Franco in 1975, Dr. Irujo remembers that the clandestine Aberri Eguna celebrations his father surreptitiously organized before and after exile became a more hopeful expression of what Dr. Irujo called “political vindication” for the loss of freedoms in the Basque Country.

“When we lived in exile in Caracas, I remember how we were dressed [in] typical folkloric dresses and danced in the Basque Center, and then how there was a political event…[and] a speech by some of the political leaders in the community,” said Dr. Irujo. “The biggest difference between the Aberri Egunas before and after the dictatorship was that these celebrations were illegal before 1975 and, therefore, people involved in the organization of this kind of political activities were at risk of being arrested, tortured, fined and exiled, which was not the case after 1978,” said Dr. Irujo, referring to a change in the constitution that afforded Basques more rights.

Now, due to the efforts of Basque political exiles like Dr. Irujo’s father, who fearlessly continued their political demonstrations of Basque autonomy and freedom from abroad, their descendants are able to remember those efforts through celebrating what became Aberri Eguna.

Jovita • Mar 5, 2024 at 6:55 pm

I’m so glad you’re informing the new generation about Basque history. I’m proud of you for your job.

Nancy Zubiri • Mar 6, 2024 at 12:16 pm

Thank you Jovita. From the Editors