Author John O’Hagan has been a lifelong fan and historian of the California missions. He left California and moved to Boise, Idaho 40 years ago to raise his family and made a lot of Basque friends there. During his research for a book about the missions, he started noticing that many of the names he ran across were Basque, with their double r’s and z’s.

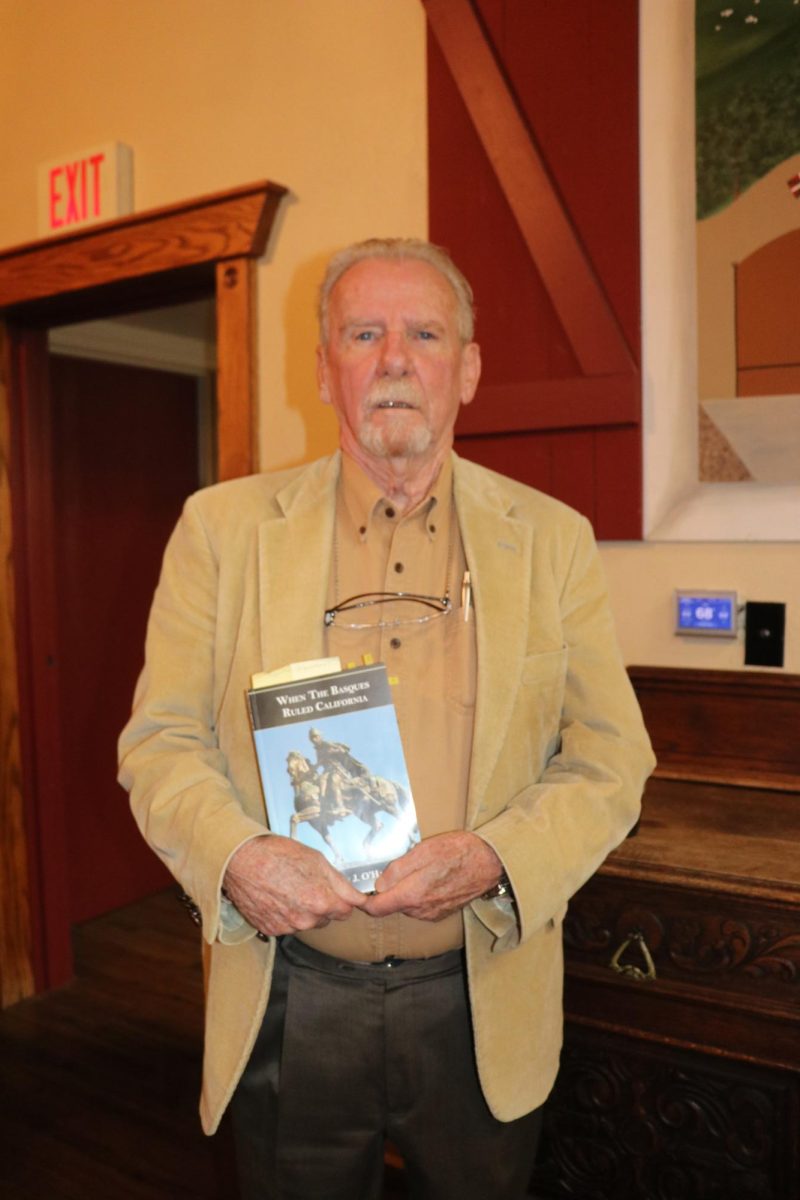

He realized that Basques had played a significant role in running the missions, the military establishments and political offices of California in its early years. In fact, Basques were governors of early California consecutively for a period of over 40 years, He wrote a book “When Basques Ruled California, 1784 – 1834” about the influence of Basques during that period under Spanish and then Mexican governance.

In an interview with Euskal Kazeta, O’Hagan was asked why he thought the Basques were such movers and shakers in the era of Spanish rule of the territory known at the time as Alta California. “The Basques claimed nobility for themselves,” he said. “That was apparently accepted in the Spanish army.” This nobility status, which was part of the Basque fueros or laws, qualified them to be officers. “The Basques filled the upper ranks of the Spanish army very likely for the simple reason that they were good soldiers, ferocious fighters and ambitious men who strived to excel in every occupation,” O’Hagan explains in his book.

O’Hagan spoke about the historical research for his book during a recent event at the Chino Basque Club, where he also signed copies of his book. Of the eight books he has authored, O’Hagan said, the one about the Basques is the top seller.

“All three seats of authority and power — military, civil and church — were for many years under the control of the Basques,” wrote O’Hagan. Father Fermin Lasuen was the head of the California missions after Junipero Serra died, Felipe de Goicoechea was commander of the Santa Barbara presidio, Antonio Bucareli y Ursua was a governor of Alta and Baja California and Jacobo de Ugarte y Loyola was the comandante general of the internal provinces — the area stretching from Texas to California and some northern states of Mexico. And many other Basques served in other positions under Spain’s rule.

O’Hagan notes that beginning in 1792, there was almost an unbroken line of governors of Basque descent: Diego de Borica, Jose de Arrillaga, Pablo de Sola, Jose Arrillaga (again) and Jose Maria de Echeandia. (Arrillaga is buried at Mission Soledad.)

The Basques’ accomplishments in California were also auspicious for the United States because they contributed to the development of the state.

“The American acquisition of California in 1846 was not a conquering of the wilderness. Instead, California in 1846 was a rich prize of towns, forts, harbors, schools, churches and agricultural and industrial complexes,” wrote O’Hagan.

O’Hagan acknowledges in his book that the Spanish conquerors of California did set out to eliminate the way of life of the indigenous people in California territory and that they were operating from a perspective of cultural superiority.

“The seventeenth and eighteenth centuries were the Age of Discovery, and discovery by a powerful European country was the end of many other established cultures,” wrote O’Hagan. “What has been referred to as “the inevitable tide of history” swept over a host of cultures in the New World and obliterated them.” However, while the mortality rate of Native Americans rose drastically due to the diseases that resulted from the colonization and the forced control of their living conditions, “the elimination of the people was never a goal,” insists O’Hagan in the book.

“The Basques whose accomplishments are touted in this book were men of education and stature in what was one of the world’s greatest powers at the time. They gave up life as privileged people in that power to labor in grueling toil in the New World; and they established, under the most adverse circumstances, settlements that today are some of the most favored places on earth. In doing that, they became implicated in the usurpation of a way of life that had existed for thousands of years.”

As part of the mission system, he notes, “the conquerors consciously, deliberately worked to train the natives in skills important to the new way of life.” The indigenous people were trained as carpenters, stonemasons, metal workers, tanners, leather workers, vaqueros and livestock tenders and in the wine industry as native vine dressers and pruners. “They were always viewed by the Spanish as potential contributing members of the new society, not as enemies to be eliminated.”

He includes a list of many projects built by the native people in California, including the construction of the oldest building in San Francisco, Mission Dolores.

“In an amazing congruence of events, dates and people, it happened that the people the Spanish Crown charged with the responsibility of for settling California and implementing these policies were Basques, or people of Basque descent,” he wrote.

O’Hagan said his initial interest in writing a book on the California missions was inspired by a trip to Italy, which included visits to many old churches. “We have churches that old and that beautiful in California, but outside of California nobody knows anything about them. I wanted to expose a greater audience to the beautiful California missions,” said O’Hagan. His first book, which preceded the book about the Basques, was “Lands Never Trodden: The Franciscans and the California Missions.”

O’Hagan’s followed his first two non-fiction books with a series of historical fiction mysteries, based on stories he heard in connection to the missions, whose main character is a Basque priest. “If you really delve into the history of the California missions, behind almost every one of those missions, there’s some horrible tale of murder and violence,” said O’Hagan. He has written four mystery novels, the most popular being “A Hidden Death at San Francisco.”

We earn a small commission from the sale of Amazon products included on this page.

Rejean Beaulieu • Jun 3, 2024 at 7:01 am

Would you be able to comment in relation to the Catalonians strong contender group throughtout the West Coast including the Pacific Northwest (prior to settlers governments)? Rf. El Pais 2020-02-24 “The-Catalans who conquered california”

Nancy Zubiri • Oct 2, 2024 at 9:08 pm

No, sorry. I know very little about the people of Catalunya in California. I know the Basques were often chosen as officers because they considered themselves noble. Their high regard for themselves led the Spanish to select them for leadership positions.

Nancy Zubiri, Editor

Bob Hernandez • Feb 8, 2024 at 1:33 pm

Thank you for this article. I am curious before buying this book – is Fernando de la Toba mentioned in this book? Not possessing what would look like a Basque name, he is often overlooked.

Born in 1774 in Sopuerta-Beci in Vizcaya, he was found in Alta California as a cadet – 1800 in Mission San Jose (present day Fremont), 1801 in Missions San Carlos Borromeo (Carmel), San Miguel and San Antonio de Padua. Fernando was promoted to alférez in 1805 and sent to Loreto, Baja California. He was listed as commander of the Presidio of Loreto in 1805 and 1807-1821. In October 1819, he supervised the interrogation of a crew of a shipwrecked whaling vessel from Britain to ensure they were not pirates. He was also governor of BC in 1814; was acting governor in 1822 when he declared Baja California independent from Spain; jefe politico in 1825-26 and again in 1837.

Nancy Zubiri • Mar 6, 2024 at 12:18 pm

I just finished reading the book and I don’t remember seeing anything about this guy, Fernando de la Toba. But the book is fascinating. Buy it from Amazon here.

Nancy Zubiri, Editor