Costume expert Ane Albisu had a hard time tracking down a bona fide bikini and miniskirt from the 1960s.

Albisu was collecting authentic items of clothing for the main exhibits of the San Telmo Museum in Donosti, which deal with Basque society through the ages. She didn’t have difficulty digging up donations of traditional Basque costumes. People realized the value of such items and had put them away in their closets and attics, Albisu said.

But old bikinis and miniskirts? Nobody had them.

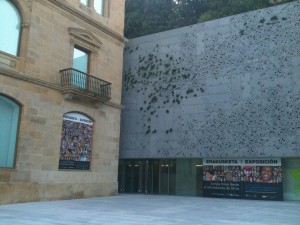

The San Telmo Museoa in Donosti, the oldest museum in the Basque Country, reopened its doors in April 2011 after a major remodeling that started in 2007. While the construction was underway, the museum took advantage of the closure to revamp its primary exhibits on changes in Basque society.

The organization Ikerfolk was consulted for help with exhibits that displayed how Basque attire had developed through the centuries. Albisu, who works for Ikerfolk, was asked to select the clothing for the exhibits. A costume designer from Donosti, Albisu specializes in traditional Basque attire.During a tour of the museum, Albisu provided insight into the many historical clothing items Basques wore that form a significant feature of this museum’s displays.

Up through the beginning of the 20th century, the whale was very important to the Basque economy for its many uses. It was even used in apparel, Albisu told Euskal Kazeta as she walked past the exhibit. Whale teeth provided the support in an early version of the corset. In fact, the corsets were called “ballenas,” which is the Spanish word for “whale.”

Tocados, or headdresses made of linen, were significant because they were commonly used by Basque women from the 13th to the 17th century. Albisu notes that each town had its own unique tocado, and each design was different.

However, despite the tocado’s importance, “not a single one remains,” noted Albisu. Consequently, the legendary fashion designer Cristobal Balenciaga created several tocados that are on display in the museum. The Basque couturier based his designs on historical artistic works.

Fashion began to play a larger role in society at the beginning of the 20th century. Even people in rural communities, who had used basic, simple traditional attire through the 19th century, began dressing like the rest of Basque society. For example, on display in the museum is the typical rural woman’s outfit of a long skirt, a big shawl and “of course, the scarf on the head,” notes Albisu.

The ’60s represented a global cultural revolution, which was also reflected in the Basque Country, in the fashions people wore. But Albisu noted that she found it much easier to collect clothes from before the ’60s.

“Antique clothing from the beginning of the 20th century was put away,” said Albisu. “But once factory production of clothes began, people threw away their clothes. I wanted a skirt that was very representative of that era, which was the miniskirt,” she said.

So Hard to Find a Miniskirt and a Bikini

“It was very, very difficult to obtain the miniskirt that we have in our collection,” said Albisu. “It was also difficult to get a bikini, which of course was an item that we saw on our beaches at the end of the 60s, and which represented such a big revolution.”

One section of the museum is dedicated to showing the switch from items made by hand – artisan work – to machine production. A prime example of that change is the rope-soled shoe known in Basque as espartinak, referred to as espadrilles in France and alpargatas in Spain. Today, certain companies continue to make them by hand, while others mass produce them.

The white alpargata with red ribbons, typical of dance costumes, were common. Albisu also found embroidered dress-up versions. But tucked away in the museum’s collection, she also uncovered a curious collection of the rope-soled shoes that she chose to put on display.

“They look like shoes. They had buckles and trim,” she noted. Because there is only one of each style, they were obviously samples made for export.

The museum also has some of the first berets made by machine. Previously, berets were knitted by hand. The early machine-produced berets were donated by Boina Losegui in Gipuzkoa, as is the vintage sewing machine.

The San Telmo Museum has a number of permanent and temporary exhibits. Among the permanent exhibits are “Memory Traces,” and “The Awakening of Modernity,” which reflect the changes in Basque apparel, plus 100 years of Basque art.

The architecture of the renovated museum has been the focus of much attention. The museum was initially located in a former 16th-century convent in a corner of the old town (la Parte Vieja) of Donosti. The renovation added a completely new modern building that connects with the old building and juts into the side of Monte Urgull, at the back of the museum. Holes have been perforated in the building walls to allow greenery to grow. just as vegetation grows from the old stones on the historic hill in back. A pedestrian pathway was developed to allow visitors to access Monte Urgull from the museum.

An open plaza in front of the museum surrounded by cafes, an ocean view and Monte Urgull make this museum a highly recommended stop in any visit to San Sebastian.

San Telmo Museoa

Plaza Zuloaga 1

Parte Vieja (Old Town)

Donosti (San Sebastian)