Jean Urruty, like so many Basque immigrants, came to the United States with just the clothes on his back. Urruty, who died in 1983, gained prosperity and left a lasting impact on the Basque community in Colorado.

He became a prominent businessman and philanthropist in Grand Junction, Colorado. He was a sheep rancher for many years and eventually, when oil was discovered on his property, his newfound wealth allowed him to engage in numerous philanthropic and civic improvement efforts.

In numerous interviews recorded with the Mesa County Oral History Project in the 1970s, Urruty described his humble upbringing. He was born in Buzunaritze, a small village of a few hundred people in the French Basque region. As a boy, he lived through the First World War, during which his father fought with the French Army.

Despite the poverty of his upbringing and the hostilities he lived through, Urruty never seemed to worry much. In his own words, “we didn’t care about Kaiser and gentlemen who were fighting… We would play handball and dance like hell and sing. Poorer than the dickens, but it didn’t keep us from staying happy.”

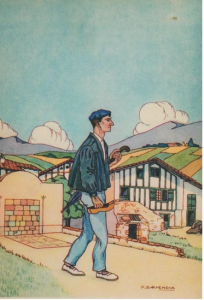

Urruty described the lifestyle of the Basques when he was growing up as “very primitive,” noting that Basques made and did everything by hand. For example, he said his mother cooked everything over a fireplace, not a stove. He spent long hours working as an apprentice for a blacksmith when he was a boy, and in Colorado, he became known for his hobby of crafting decorative items out of wrought iron later in life.

An illustration by Pedro Garmendia from the book Tales of a Basque Grandmother, a collection of tales by folklorist Frances Carpenter, shows the style of costume that Urruty said was customary in the Basque Country during the time of his youth.

When he was a young man, he followed in his father’s footsteps and served in the French Army, which was obligatory for all young men in France at that time. He served one year in Bordeaux in 1924 in a mixed division with Senegalese from Africa. (Senegal was then under French rule.)

In 1925, like so many countless other Basques both before and after him, Urruty came to the United States in search of economic opportunity that did not exist in the Basque Country at that time. Because of strict American immigration laws at the time, Urruty had some difficulty getting to America. Nevertheless, with the help of a travel agent, he said, he was the only Basque on a boat filled with about 900 German immigrants, many of whom were engineers, which landed at Ellis Island in New York in 1925.

He recounted these experiences in an interview that is now in the collection of the Library of Congress, and can be viewed or listened to here: Jean Urruty, Library of Congress Interview

In New York City, he boarded a train and headed west to meet his cousin, Grace Aubert, in Price, Utah, according to another interview he gave with the Mesa County Oral History Project. He avoided the state of Nevada, as he had heard stories of cowboys terrorizing Basque sheepherders there. In Utah, he worked for about five years as a sheepherder, which he described as “a very lonesome trade.” As a sheepherder, Urruty would keep himself occupied by carving wooden figures as well as by carving into aspen trees, an activity that many Basque sheepherders partook in and whose markings in many cases are still visible today.

After several years as a sheepherder, he and some other Basques became partners and purchased 3,000 sheep of their own with a loan from a well-meaning Italian banker. Remarkably, they did this during the Great Depression, the worst economic crisis in American history. However, economic troubles were not the only hardships that Urruty faced. In 1932, his partner was shot and killed, and local funeral homes would not bury him. As a result, Urruty, who did not speak English well at the time, had to bury him himself.

In 1935, he met the woman who would become his wife, Benerita “Bennie” Velasquez of Colorado, who was of Native American heritage. They met at a carnival in Grand Junction, at which they rode a Ferris wheel that broke while they were on it, as Urruty recounted in an interview between giggles. They married on June 27, 1935. A few days later, on July 1st, the newlywed Urrutys ventured into the hotel business when they bought the LaSalle Hotel in Grand Junction, a historic building that was by then already 80 years old. They owned the hotel for 20 years. Buy Echeverria’s book on Basque boardinghouses from Amazon.

The two kept the hotel “immaculate clean” and contributed to the development and beautification of the surrounding area of town by paving the dirt road of Colorado Avenue, the original main street of Grand Junction, said Urruty in the interview with the Mesa County Library.

He also said he worked with the local police to clean up the rough neighborhood. Throughout his assorted career, Urruty always maintained his belief in the dignity of hard work, instilled in him from a young age in the Basque Country.

In an interview, Urruty recounted how in the Basque Country, “We would get up at 4 o’clock in the morning, work till nine or ten at night… To work here was nothing for me, just to play. Hardest work in the United States was nothing compared to the way we work over there.”

Urruty eventually became an established and well-respected figure in Grand Junction and the surrounding area. When oil was discovered on his property in the 1960s, his wealth also allowed him to engage in numerous philanthropic efforts.

For example, in the 1970s he financed the college educations of four local young women, gifting each with a $10,000 scholarship. In addition, he paid for a young man from the area to attend law school. For these and other charitable efforts, he received the coveted Americans by Choice Award in 1976, “given to naturalized citizens who have distinguished themselves by community service,” according to a 1977 story by The Palisade Tribune in Mesa County.

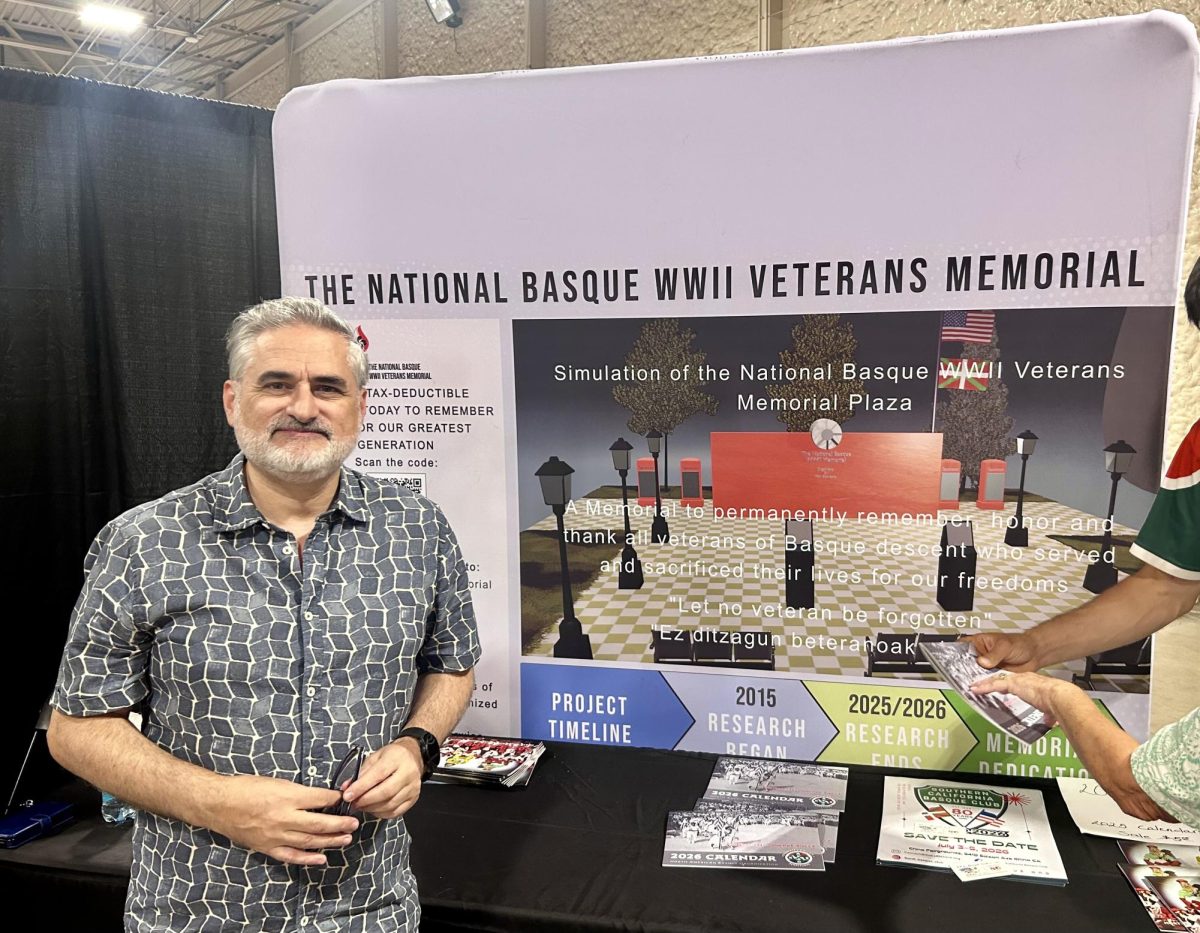

Despite his reputation among the general populace of Grand Junction, Urruty’s legacy is most meaningfully remembered by Colorado’s Basque community. In the 1960s, he founded the Western Slopes Basque Association, through which Urruty organized festivals and other gatherings for the area’s Basque residents. One such festival was the Twelfth Annual Basque Festival in Grand Junction, Colorado, which was partially recorded by the Mesa County Oral History Project. On this recording, much of the festivities and celebrations of the day can be heard, including accordion music, singing, dancing, and many boisterous irrintzis (Basque war cries). According to Urruty, the history of the irrintzi dates all the way back to the Middle Ages and was used during the Hundred Years’ War as a signal that the English were coming.

On the tape, Urruty also explains his intense pride for his Basque culture and for the Basque Country from which he came. In his own words, when asked if either the French-Basque or the Spanish-Basque culture would be on display, he flatly responded: “It’s only Basque!” He explained further using the following analogy: “If you plant a carrot seed, you’re not gonna raise onions. We’re born Basque and we’re going to die Basque!”

The attendees of the festival certainly had great respect for Urruty. In the interview, one attendee named Bill Daguerre said of him, “He’s our president. He’s the president of the Basque people” in the Colorado area. “We do whatever he tells us to do… He’s a great man, as far as I’m concerned.”

Urruty was such a prominent figure that he even starred in a documentary film entitled The Basque Sheepherder. The film chronicles three years in the life of a Basque sheepherder who comes to work for Urruty in the Colorado mountains. It can be viewed in its entirety in the Youtube video above. (Urruty enters the picture at around the 15 minute mark.)

Even though Urruty died more than 40 years ago, his legacy lives on, most notably through Plaza Urrutia, the handball court that he built in 1978 and still stands today as a monument to him and his contributions to Colorado’s Basque community. See our story about this handball court.

The interviews that the Mesa County Oral History Project conducted with Jean Urruty in the 1970s can be listened to in full at the link below: