The Bilbao Effect – Reviving a City Through Art

July 31, 2011

My trip to the Basque Country did not include a long to-do list. I haven’t been here in 16 years, yet when I arrived two weeks ago, I did not feel compelled to do a lot of sightseeing. I only wanted to attend a family reunion and visit with friends. With the exception of one excursion: a visit to the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbo, as Bilbao is called in Basque.

When I was in Europe last, in 1995, the plans for this massive architectural jewel were already in the works and quite controversial. The primary question then: Why Bilbao?

When I was in college, during 1979, I spent quite a bit of time in the Basque Country – mostly in Iparralde – the French side – where my immediate family is from, and a bit in Gipuzkoa. Never in Bizkaia. Bilbo had a tradition of being a very industrial city, and I was told factories poured their wastes into the Nervion River that runs through it. Local friends disencouraged me from visiting, claiming there wasn’t much to see here.

The construction of the Guggenheim changed that image. The museum, which opened in 1997, has brought millions of new visitors. The biggest Basque city has become a must-see stop for international travelers.

In fact, it is referred to in news reports as “the Bilbao effect” -– the regeneration of a city, led by art.

“Despite attempts to emulate the ‘Bilbao effect’ elsewhere in the world, very few new museums or galleries outside capital cities have succeeded in getting so many visitors. Gehry’s architecture and the Guggenheim’s art have proved an irresistible combination,” a Forbes magazine declared in 2002. This article unfortunately does not take into effect what I call “the Basque factor.” The Basques have survived over the centuries because of their ability to take what is there and work hard at making it better, yet making it theirs at the same time. (Euskadi is an economic cornerstone of Spain. Those who left the Basque Country have found economic success and perpetuated their culture in their new homes.)

The fact is that the construction of the Guggenheim Museum was only one part of the redevelopment of the city. Bilbo, the biggest city in the Basque Country, was already attempting to change its image from that of an industrial port to a vibrant city. A plan for a major clean-up of the river had already been developed in the 1980s.

The Guggenheim Museum

Admittedly, none of the exhibits we saw were specifically Basque. Yet that is as it should be. The museum is international in scope. However, the Basque influence is ubiquitous. The explanations for all exhibits are in Spanish and Euskera. The main signs for visitors are in Spanish, English, French and Euskera. One of my 10-year-old son’s favorite sightings in the museum was the longest Basque name he had ever seen.

The exhibits accomplished their objective. No easy explanations for most of these modern, unusual artistic installations lead visitors to wonder what is the point and question their own thoughts and ideas. The majority of the exhibits we saw were part of “The Luminous Interval,” a private collection of contemporary art that will be here through Sept. 11.

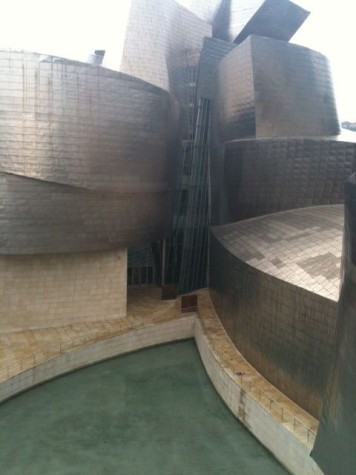

The best feature of the museum is without a doubt the building itself. Inside and out, the design creates different, magnificent views from every single spot. Architect Frank Gehry explains through the free multilingual audio guides offered to visitors that nothing except the floor is straight. All lines curve. Much of his inspiration for the museum’s design, he relates, came from the fish he brought home from trips to the market with his grandmother, then put into the bathtub until it was time to cook them.

Gehry explains too that part of his goal of placing the museum on the edge of the Nervion River was to have the building itself bring people to its doors. Our personal experience is a testament to his success.

The museum is fairly easy to locate because of its high visibility from many parts of the city. We parked on the opposite side of the river in a parking structure under the elegant Hotel Hesperia. After thoroughly enjoying a classic almuerzo at the Cafeteria Mandobide in the Plaza Funicular, we were directed by the friendly manager to the tree-lined walkway along the river then up the elevator to the top of the Puente de la Salve, built in 1972, whose red arch was added in 2007 by artist Daniel Buren. At the top, we had a stunning view of the shiny titanium-plated architecture.

MORE FROM Euskal Kazeta

What to See in Bilbo

Basque Restaurants in the U.S.

The Best Basque Restaurants in the World

The City of Bilbao: A Revival and Evolution

Basque Identity and Athletic Bilbao’s Success

What to See in Donosti (San Sebastian)

The picturesque red La Salva bridge, which is a sight to see in its own right, led down to curving sidewalk around the building to the front of the museum, where a giant pink, red, yellow, purple and white-flower-covered puppy greets visitors. During our visit, many windows and skylights encouraged us to look upward and down. Glass doors in the museum lead to many open spaces where sculptures, water and views encourage visitors to linger. It was a rainy day in the middle of the summer – a moment likely to create a packed house. Yet the Guggenheim never felt crowded, due to the many options and directions available at any point in time.

Consider eating at Nerua, an award-winning restaurant inside the Guggenheim. Here’s a behind-the-scenes video about Nerua.

All in all, the Bilbao effect, coupled with the “Basque factor,” made our visit to this cosmopolitan city one we will readily repeat.

Hours and Admission at the Guggenheim Museum

Donate

Donate

Frank Lostaunau • Apr 22, 2013 at 2:49 pm

Listing of Basque Artists:

http://en.classora.com/reports/i360122/who-are-the-best-contemporary-artists-from-basque-country-%28euskadi%29

Frank Lostaunau • Jan 14, 2013 at 3:38 pm

There has been a tiny tiny tiny tiny itsy bitsy increase by Guggenheim curators to include more Basque artists…don’t expect much…it’s 2013 and there has been enough time for that to have happened…don’t waste your time hoping for it to improve…consider seeing the Basque Country, as much as possible, that is infinitely more interesting…Americans are mostly interested in fellow Americans…not much more…

Frank Lostaunau • Nov 17, 2012 at 6:03 pm

Photogravure by Unai San Martin: http://www.smithandersennorth.com/artists/san_martin/index.html

Frank Lostaunau • Nov 8, 2012 at 4:22 pm

http://www.basquecountry-tourism.com/culture-museums-vitoria-artium.php

Contemporary Basque Art!!!!

Frank Lostaunau • Nov 8, 2012 at 4:17 pm

art: http://www.yturralde.org/Paginas/Etapas/et01/index-es.html

Yturralde!

Frank Lostaunau • Oct 9, 2012 at 5:01 pm

Gordon Matta-Clark was of Basque, Spanish,French descent:

http://secretforts.blogspot.com/2011/01/anarchitect-gordon-matta-clark-1943.html

Frank Lostaunau • Sep 8, 2012 at 12:23 pm

List of Basque artists. Click on the names and view beautiful art!

http://www.artfacts.net/en/institution/artium-centro-museo-vasco-de-arte-contemporaneo-2657/overview.html

Enjoy!

Frank Lostaunau • Sep 8, 2012 at 12:17 pm

Contemporary Basque Art: http://www.e-flux.com/announcements/goose-flesh-by-regina-jose-galindo/

Frank Lostaunau • Sep 8, 2012 at 12:10 pm

Enjoy the work of a Basque artist!

http://zuloartifiziala.wordpress.com/2012/06/01/carmelo-ortiz-de-elguea-as-a-main-figure-of-the-basque-school-and-founder-of-orain-group/

Frank Lostaunau • Sep 3, 2012 at 6:14 pm

yup! I agree…go back more often and you’ll feel more whole!

My suggestion…stay out of the googooheim…it has failed miserably to pay tribute to the struggles of the Basque people…also, it’s possible to catch an eye fungus if you simply step inside…view the structure from a bridge, think about it when you’re on the pot…then, moveon.com…you’ll live a longer and happier life! GORA GORA!

Frank Lostaunau • Sep 2, 2012 at 9:47 pm

The architecture is impressive!

It’s my impression that the curators do not believe that there are Basque artists whose work merits exhibition in the museum.

The presence of the museum has indeed boosted the economy of Bilbo. However, I will never return unless museum exhibition becomes more inclusive. There are Basque artists whose work merits exhibition. However impressive the structure, the people, the culture and the country is much more nurturing and wonderful. Skip the museum, it’s a waste of time.

Cynthia Thompson • Jun 22, 2012 at 10:21 am

Wow, what architecture! The museum building is so different from anything you find in most cities. It was a really worth the visit. Incidentally, I think it would make more sense to include a section dedicated to Basque exhibits in the museum as well. The fact that it is in the Basque country would raise the expectations of the visitors that some dedicated Basque exhibits be there as well.