The battered statue on the scrub-covered plain in Reno has seen better days. The abstract work of art — a shepherd carrying a lamb over his shoulders under a full moon — is dedicated to the pioneering, industrial spirit of thousands of Basque sheepherders, who roamed the mountain meadows and harsh desert plains of the American West.

On August 27, 1989, over 1,000 members of the Basque community gathered on the hill at Rancho San Rafael Park to dedicate the National Monument to the Basque Sheepherder. Many of them were family members who donated money to put up the memorial to have their fathers or grandfathers’ names inscribed on a wall next to the statue. It was a proud, historic moment. It was a memorial that visitors would appreciate for years to come.

But today, the monument is in disrepair. It’s scarred by graffiti. Sometimes, empty beer bottles and trash are strewn amid the scrub brush.

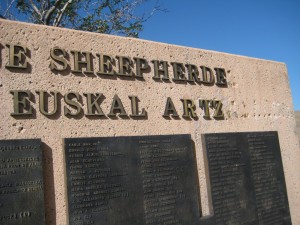

On a recent morning, the work of vandals was evident. Graffiti — scrawled with markers or etched into the bronze statue with sharp objects — covered the base of the 22-foot high work of art. Several plaques around the statue are supposed to guide visitors on an interactive experience. But due to weather or vandalism, the information has disappeared. On the wall listing donors’ names, letters have fallen off the “Euskal Artzainak” sign.

Part of the problem is its isolated setting, on Peavine Mountain, away from the beaten path. But this location was a deliberate choice. “It’s called Solitude,” said Professor Carmelo Urza, part of the original organizing committee and author of a book on the monument Solitude. “It’s a rural setting and there were sheepherders there,” he noted, referring to the Basque herders who once grazed their sheep on the mountain. Urza noted that in previous years, he and Professor Bill Douglass even visited the site with buckets to pick up broken glass.

“Trash and graffiti is always going to be a challenge,” said Bob Harmon, spokesman for the Washoe County Regional Parks and Open Space. “You have to have it accessible to the public — that is the point, but it’s a double-edged sword.”

Park staff members visit the location two to three times a week to empty the trash can and check on the area, he said. They keep an eye out for large or offensive graffiti, but sandblasting or using a cleaner on such marks can leave a stain on the monument.

“There’s only so much that we can do,” said Harmon. “We don’t have the expertise for museum-style art repair.” He pointed out that the district has insurance on the statue and can file a claim to replace the missing letters or clean the statue appropriately. What they lack is knowledge on what to do about the scratched-on graffiti.

sheepherder experience are missing.

Urza agrees, noting that the patina on the bronze statue could be destroyed. Staff members at the Center for Basque Studies need to find or rewrite the information for the missing reader boards, he noted. And they need to find an expert who knows how to remove the graffiti safely.

The project was a significant endeavor for the international Basque community. It was the first time that such a monumental, community-wide project was undertaken, noted Jose Ramon Cengotitabengoa at that time. He was president of the nonprofit Society of Basque Studies in America, which spearheaded the project.

The organizing committee sought financial support from Basque officials in Europe for part of the $350,000 needed to develop the memorial. The other half the money was donated by former sheepherders and their relatives, in small amounts.

An international competition was held to select the artist. In the end, the committee chose acclaimed Basque artist Nestor Basterretxea. Ultimately, he titled his 22-foot high, five-ton bronze masterpiece “Bakardade,” or Solitude.

Like other major initiatives involving many people, the effort was not without controversy. Some in the community — including several committee members — were unhappy with the abstract design. They would have preferred a more figurative representation. But ultimately the design committee chose Basterretxea’s design because the modern artistic language was considered more appropriate for the 21st century.

Many people have visited the site over the years, including a number of Basque government officials.

Both Harmon and Urza envision some kind of joint effort between the Center of Basque Studies at University of Nevada Reno, the local Basque club and the parks district to bring the monument back to its former glory.

Hopefully, noted Harmon, they can pull together a team

of volunteers “to give it some tender loving care, which it can really use right now.”

To reach Carmelo Urza, call the University of Nevada Reno at (775) 784-6569.

Related Articles and Books

Article (2000) from the Center for Basque Studies on the monument and the artist

Article (1988, Issue 38) from the Center for Basque Studies on the monument

Solitude: Art and Symbolism in the National Basque Monument by Carmelo Urza